Since all three names, Ackland, Langstaff and Warren

derive from old English families tracing their ancestry

back to Norman conquest it seems fitting that the journey

begin with a short history of the impact of English

colonization on the Irish people. Good luck surfaced two

old family histories on the Warren's and the Langstaff's,

but nothing on Ackland other than it was a common name in

Devon, England. The name Dormday, Hugh Ackland's wife's

name, is intriguing in that to date no other instance of its

use has been uncovered and I still leave queries concerning

it on any relevant web sites I visit.

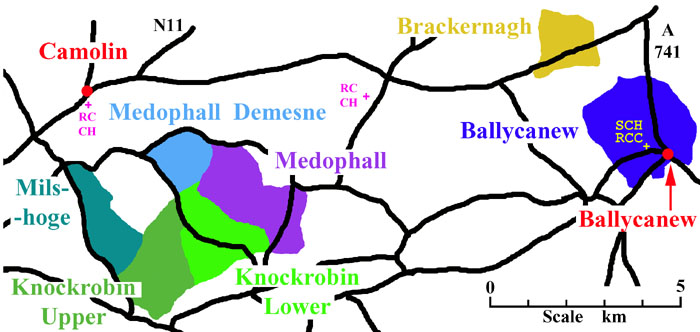

3 The map to the left shows the five dioceses of the Dublin

Ecclesiastical Province. Also shown are the city of Dublin to the north

and the port of Wexford to the south of the village of Ballycanew where

William and Elizabeth were married. It should be noted that William's

brother John and his wife Dorothea "Dolly" Whitmore were married

in Ballycanew as well.

The Norman Conquest and Early Langstaffs and Warrens

The English have been in Ireland from Roman times and records are sketchy. From

the death of King John, of Robin Hood fame (1216), the English have controlled to

greater or lesser extent the lands to the east of County Cork in the south and east

of the river Maine. Norman Knights were awarded estates in Ireland as rewards for

their support of the King. One such knight was William de Warrenne, first Earl of

Warren and Surrey, who had considerable command at the Battle of Hastings (1066)

probably due to the fact his wife, Gundreda, was William the Conqueror's daughter.

No record of his having Irish possessions exists, and I mention him only as one of

the earliest recorded Warren's and to show our journey from the continent (Normandy)

via England to Ireland and eventually Canada.

The earliest English Langstaff reference appears in 1219 when the Sherriff of

Norfolk was commanded by oath of 12 knights and free tenants of Panneworth and

Nereford (located a few miles north of London) to make diligent inquiry whether Issac

of Norwich and twenty other persons, among them John of Nereford, Langstaff, Roger

de Chively ...William Scolet...and Moses the Jew, did destroy and waste the chattels

of Peter of Nereford4. The record does not make clear if Langstaff was a servant of

Issac the Jew nor is the issue of Langstaff's guilt or innocence resolved. But the

name is definitely recorded. Not John or William Langstaff, just Langstaff as if he

was a Peer as surnames were uncommon among poor folk at that time. This man may be

the first to bear our name and did he bear it because he wielded a longer quarter

staff than his compatriots? It begs the imagination to wonder if he knew Will

Scarlet (William Scolet) again of Robin Hood fame.

4 From the book "The Langstaffs of Teesdale and Weardale: materials for a

history of a yeoman family gathered together by George Bludell Longstaff,

M.A., M.D. Dron, F.S.A.

In many cases when English Nobles took possession of their land it had to be by

force, i.e. to subdue the local population and in many cases supplement it with

soldiers and retainers from England. Thus one source of our Langstaff's and Warren's

ancestors was probably among these soldiers and retainers that accompanied the

Knightly and Gentlemen families as they were probably not of the class destined to

receive landed estates. In turn, these folk originally taken for protection and

settlement inherited certain rights to land that could be passed on to their offspring.

By this account we could have been in Ireland since the 11th century.

The Elizabethan Era

The next possible origin comes in the Elizabethan era especially after the wreck

of the remnants of the Spanish Armada in 1588 on the Irish coast. Under Elizabeth,

many English gentlemen and their families were given huge estates in order to pacify

the rebellious local Irish population and to reward loyal subjects. Some of these

families could also trace their origins back to the Norman invasion of 1066. These

settler families were called "undertakers" as they were required to undertake certain

conditions set out in the Queen's articles in order to retain possession of their

awarded estates. Well worth the effort when one sees that families received between

3,000 and 6,500 acres and the accompanying inhabitants as their allotted estate. One

knight, Sir William Herbert, was given the ridiculous amount of 13,276 acres. Again,

our Langstaffs and Warrens were probably not of the class destined to receive landed

estates but they were possibly among the retainers, farmers, and tradesmen, that

accompanied the Gentlemen families to provide for their comfort and livelihood.

Records show there was a Warren5 settler family in Tralee, Co. Kerry from Elizabethan

times until the rebellion of 1641. As well Sir Edward Warren of Poynton, Cheshire, was

knighted for service in Ireland in 1599 and presumably moved his family there as his son

Edward is registered at Trinity College, Dublin in 1604 and later becomes Dean of Ossory

(the parish where William and Elizabeth's marriage is recorded).

5 The Families of County Kerry Ireland: Michael C. O'Laughlin, Isbn: 0940134-36-5,

published by Irish Genealogical Foundation, Box 7575, Kansas City, MO,

USA 64116, © 1994

The Cromwellian Confiscations

The next English invasion took place in the 17th century when the Ulster Irish

rebelled in Oct. 1641 and supposedly murdered thousands of the old English settlers.

Even at this time there was a tremendous variety of Anglican English, Anglican

Anglo-Irish, Catholic Anglo-Irish, Catholic Irish and Presbyterian Scots who could

trace their heritage back many generations and who considered themselves true

Irishmen to the core. In many instances their land was confiscated by the Government

in London and given to the new wave of settlers. It was for this reason they rebelled

and the "massacre" of English settlers and their families took place. History records

no true evidence of such killings(See Walter D. Love's "Civil War in Ireland:

Appearances in Three Centuries of Historical Writing", but stories circulated by

relatives of the dispossessed, Parliament, and the press of the day played it up and

it had a great effect on Cromwell and his generation. Thus on the 15 Aug. 1649,

Cromwell landed in Ireland with an armada of over 113 ships. When he destroyed the

town of Drogheda his forces there numbered 8,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry. The

fighting continued until late 1652 and by that time an estimated 600,000 Irish had

been slain. As well his march route took him directly through County Wexford where

the Warrens and Langstaffs were or would later be located.

In order to pay for the invasion 2 million acres of land was confiscated from any

"Irishman6" unable to show that he had supported Cromwell's Commonwealth and not

Charles I and the Catholic cause. From this there resulted a new English landlord

class that would last until modern times and a mass exodus from Ireland of mainly

Catholic Clergy and the defeated military. The land went to those who could pay, in

fact Cromwell himself paid £2000, a very large sum in the 1600's, in three installments

of £600, £600 and £850 for land in the barony of English.

6 Great families of pure Irish blood were rare even by this time.

Most wealthy families traced their lines back to English or

Norman roots.

The evidence of Langstaffs in Ireland from this period is slight and only one event

was found, that being the will of one Christopher Langstaff (see Appendix XV, Langstaffs

of Teesdale and Weardale, page cclvii), a clothier from Dublin whose will was proven on

26 April 1671. Bequests to people in Leeds Yorkshire (see John Longstaffe7, Leeds,)

show there was still a strong English connection between the families and the move to

Ireland was more recent. Is it possible that our Langstaffs were somehow involved with

Cromwell's army and received land in that manner.

7 Records of John Longstaffe and his many works and his Quaker troubles are

from the Langstaff book, and possibly from Joseph Besse's 1753 book,

"Sufferings of Early Quakers in Yorkshire: 1652-1690", see pages 127-8, 154.

From the "Warren History" there are many instances of Warrens spread over the

counties of Dublin, Cork, Queen's, Meath, Kildare, well before and after the invasion.

Thus this family could very well be of old settler origin as well as part of these

events.

Religious Troubles in England

During the 17th century there occurred many instances of religious persecution.

Was this then a reason to leave England? Puritans had left as early as 1608 for

America but many also moved to Ireland. In Joseph Besse's 1753 book, "Sufferings

of Early Quakers in Yorkshire: 1652-1690", several Langstaffs and Warrens are

mentioned; e.g.

1) 1655 John Warren beaten on the Highway;

2) 1670-71 Kirkton, Anne, Elizabeth, John, and James Langstaff fined

10s to 2£ for attending meeting;

3) 18 Nov. 1683 in Leeds, Daniel (clothier, same occupation as Christopher

in Dublin), Sarah , and John Langstaff were part of a group of fifty

persons jailed for four days and nights without food, water or heat for

attending meeting, as well goods to the value of 6£ 9s was taken from

John Langstaff and John Waites;

4) 1684 Scarborough, goods valued at 3£ 18s 8d taken from William Warren

for attending meeting.

These folks had the courage of their convictions and it is possible they did settle

in Ireland to escape the oppression by the established Church of England.

Jacobite War and William of Orange

The next event that bears on our family occurred after the expulsion of Catholic

James II from the throne of England8 in favour of hopefully a more religiously tolerant

Protestant William of Orange in 1688. In 1689 James and his French supporters fled to

Ireland where he raised the hopes of the Catholic majority for the return of property

and privilege. Only Londonderry and Enniskillen, two Protestant cities in the north,

remained loyal to the English cause.

8 Some of the following material came from these two books:

1) Ireland, A History by Robert Kee, Weidenfeld & Nicholson Ltd., London;

2) Landlord or Tenant, Magnus Magnusson, The Bodley Head, London.

The famous "Siege of Derry" began on Dec. 7, 1688 when 13 Protestant "apprentice

boys" seized the keys to the city and closed the gates in the face of James' troops.

A Catholic regiment known as the "Redshanks" led by Lord Antrim then proceeded to block

the entrance to Lough Foyle, the naval approach to Londonderry and proceeded to starve

the populace into surrender. Inside Londonderry were at least 30,000 Protestants,

sitting targets, unwilling to be starved out. However, James had no siege artillery so

from April to July the townspeople were peppered by mortars that riddled the town slowly

to pieces while the inhabitants ate everything in sight, including dogs, cats, mice,

candles, and leather. The wet summer meant that disease was also rampant and more

people died as a result. The siege was finally lifted on July 28, 1689 when James

British ships broke the blockade and relieved the city.

The Catholic cause was further diminished the next year, 1690, when William of

Orange himself landed at Carrickfergus Castle and won a "great" victory over James at

"The Boyne". At the River Boyne on the 12 July, William's English, Dutch, and French

Hueguenot (i.e. Protestant) regulars as well as mercenaries from Denmark, Prussia,

Finland and Switzerland, 14,000 in all, routed 21,000 Catholic French and Irish troops

but James escaped to France, and the war dragged on for another year. On the

22 July, 1691 at Aughrim, Co. Galway, the combined French and Irish armies were finally

defeated. A formal peace was concluded when the Irish, under their old English Gaelic

Catholic commander, Patrick Sarsfield, surrendered on 22 Oct. 1691 at Limerick.

Thousands of Sarsfield's troops were allowed to return to France to fight under Catholic

Louis XIV as "Wild Geese". This was the triumph of the "Orange" over the "Green" still

celebrated in Ulster pubs today. In reality this war was only a skirmish in the struggle

going on in Europe at the time between the French Bourbons and the Hapsburg of

Austro-Hungary, with England and Ireland on the sidelines. However, these religious

overtones continue to affect Irish life to this very day.

That the Langstaffs were involved in these events can be surmised from the Minutes

of Monthly Meeting of Quakers held at the home of John Longstaffe7 "The Quaker Contractor"

in Raby, Yorkshire where it is recorded on May 7, 1691 that a William Francis and a Mary

Raines, recently from Ireland, were granted permission to wed. They having recently

escaped the troubles and desolation in Ireland had no certificates (one assumes baptismal

records), the Battle of the Boyne having taken place in the preceding year. As

previously mentioned many Yorkshire Langstaffs suffered fines and imprisonment for

their Quaker beliefs and it is readily imagined some may have left England for Ireland

to escape what they referred to as the "popish church". However, our ancestors were

all members of the Church of England in Canada and records also show many Langstaffs

remained loyal to the state church.

The Popery Code or Penal Laws and the 1798 Rebellion.

With James' defeat and the signing of the Treaty of Limerick the Catholic cause in

Ireland was crushed and to ensure its demise, the ruling Protestant minority enacted a

series of anti-catholic laws known as the "Popery Code", today called "The Penal Laws".

These laws were designed by the Protestant Irish Parliament to ensure that Catholic

Ireland would never again endanger the safety of Protestant England. While the Articles

of Limerick had granted Irish Catholics the right to exercise their religion consistent

with the Laws of Ireland, this new code set out to degrade the Catholic majority, and to

emasculate the remnants of the Catholic landed gentry. Some of the major articles are

listed below:

1) No Catholic may sit in parliament;

2) No Catholic may be a solicitor, game keeper, or constable;

3) No Catholic may possess a horse of greater than 5£ , any Protestant offering that sum

may take possession of the hunter or carriage horse of his Catholic neighbour;

4) No Catholic may attend a university, keep a school or send his children to be educated

abroad. A 10£ reward is offered for the discovery of a Roman Catholic schoolmaster;

(the origin of the "hedge row" schools where Catholis schooling took place outdoors)

5) No Catholic can buy land or receive it as a gift from a Protestant;

6) No Catholic may bequeath his estate in whole, but must divide it among his sons, by

the system known as "gavelkind ", unless one son becomes a Protestant, whereby

he will inherit the entire estate; (Under common law the eldest son excluded his

brothers, by gavelkind all sons shared equally. Normally this law applied only if

the father died intestate. Encyclopedia Britannica.)

7) No Catholic may be a guardian of a child; orphan children of Catholics must be brought

up as Protestants;

8) Catholics were excluded from the vote.

The laws did not prevent, as commonly supposed, the worship of the Catholic faith, but

banned from Ireland, under pain of transportation or even death, all Catholic Bishops,

Archbishops, and friars of the regular orders (Augustinian, Dominican, etc.). Only Parish

priests were allowed to remain. With no hierarchy to ordain new priests, it was supposed

that the Catholic church must eventually die out.

While the Popery Code or the Penal Laws were meant to remove the Catholic Church

from Ireland, little attempt was made to enforce the code. It was really a matter of power,

not religious piety. Besides, the fact that the vast majority of Irish people were in support

of the Catholic Church made enforcement well nigh impossible. So by the middle of the 18th

century the Catholic Church, though it officially had no churches, was back to full strength.

The Protestant minority turned a blind eye on the makeshift places of worship, and services

were held openly in stables, warehouses, and in the open air in the lee of the hedgerows.

These latter became known as "hedge-masses ", similar to the "hedge row" schools. There

are still sites in Ireland today that supposedly mark outdoor "rock alters".

The "sacramental test" administered under the 1704 Bill had one unforseen result. The test

stated that if one did not take the sacrament as prescribed by the Established Church of Ireland

one could not hold office of trust or profit. This excluded from Parliament etc. the Ulster

Presbyterians who up till then had been in control, especially in the cities of Belfast and

Londonderry. This played a significant role in the mass emigrations of the late 18th century.

These laws remained completely in force until 1778 when the first of the Catholic Relief Acts

extended significant benefits to Catholics who took a new oath of allegiance to the crown.

At this time there was still much animosity between the Catholics, organized as "the defenders"

and the Presbyterians organized as "the peep-of-day boys" (so called for their early morning

visits to Catholic families to collect arms). Wanton outrages were committed by both sides

especially in the northern counties. The local gentry, for electioneering purposes, did little to

stop these outrages.

The French revolution of 1789 caused the Irish establishment to close ranks once more with the

English. But in 1791 a young Protestant Dublin barrister, Theobald Wolfe Tone, founded a

movement called the United Irishmen, composed of members of the Catholic Committee and

what were known as Presbyterians (Protestants, not of the Church of Ireland, committed to the

establishment of a democratic Ireland). It was formed in both Dublin and Belfast and its objectives

were to rid Ireland of English influence once and for all. The movement had to be secret for it was

quickly shown that reform would only be achieved by force, not persuasion. In fact riots broke out

all over the land and Catholics battled Protestants for possession of the land. It was during one of

the larger riots in 1795, the battle of the Diamond, where at least 30 people died, that the victorious

Protestants formed a new society, the Orange Order, to defend their land and religion.

Wolf Tone's United Irish movement was in trouble as it was clear the Irish were in reality anything

but united. A large part of the organization was made up of an older Catholic society, "the defenders",

and they were more dedicated to the establishment of Catholic rule for Ireland. The secret society

was now not so secret and due to informers the English military were quickly arresting all suspects

and with the liberal use of torture (standard punishment, between 500 and 999 lashes) were

uncovering the entire movement. Wolf Tone had gone to France for help and in 1796 a French fleet

of 43 ships with 15,000 men attempted to land in Bantry Bay. The "elements" were opposed and

a huge winter storm scattered the French fleet and the British had a narrow escape. This caused an

increase in the crackdown on the United Irish in Ulster and elsewhere in Ireland. By 1798 the United

Irish felt they had to act or lose the chance. Accordingly they launched rebellions in County Down

and Antrim in the north and County Waterford and Wexford in the south.

In County Wexford, according to L. M. Cullen, the rebellion resulted purely from economic unrest

and the leadership was local middle-class people drawn into the movement after it had begun. Of

those leaders, two are relevant to our history.

The first was Fr. Michael Murphy who had been dismissed from the priesthood and was in contact

with the United Irishmen and lodged in Ballycanew. On learning of the uprising the local Camolin

Yeomanry burned his lodgings and shot his landlord. This event took place almost on the Langstaff

doorstep (see townlands map above for distances, townlands are like our townships but generally

much smaller and as you can see very irregular). Father Murphy is buried in the cemetery of St.

Edans Cathedral in Ferns (see photo below).

The first was Fr. Michael Murphy who had been dismissed from the priesthood and was in contact

with the United Irishmen and lodged in Ballycanew. On learning of the uprising the local Camolin

Yeomanry burned his lodgings and shot his landlord. This event took place almost on the Langstaff

doorstep (see townlands map above for distances, townlands are like our townships but generally

much smaller and as you can see very irregular). Father Murphy is buried in the cemetery of St.

Edans Cathedral in Ferns (see photo below).

The second was a Fr. John Redmond of Camolin (just west of Medophall townland), identified as

an "orange priest" because of his anti-rebel sympathies. He was forced to take refuge in Protestant

homes during the course of the rebellion.

From these two individuals, one Protestant and one Catholic, one can see that no matter which

side you were on, your life and the lives of your family were in constant danger.

A chronological description of the main events of 1798 that took place in the vicinity of the

Langstaff townlands follows:

30 Mar: Martial law declared over all Ireland and the local Yeomanry and Militia terrorize the people

with scourging, pitchcapping (covering the head with pitch and setting it alight, common in

Ferns, Gorey area), and half-strangulation;

The second was a Fr. John Redmond of Camolin (just west of Medophall townland), identified as

an "orange priest" because of his anti-rebel sympathies. He was forced to take refuge in Protestant

homes during the course of the rebellion.

From these two individuals, one Protestant and one Catholic, one can see that no matter which

side you were on, your life and the lives of your family were in constant danger.

A chronological description of the main events of 1798 that took place in the vicinity of the

Langstaff townlands follows:

30 Mar: Martial law declared over all Ireland and the local Yeomanry and Militia terrorize the people

with scourging, pitchcapping (covering the head with pitch and setting it alight, common in

Ferns, Gorey area), and half-strangulation;

25 May: Under torture Anthony Perry implicates several Protestants (Bagnal Harvey, Edward

Fitzgerald, John Colcough) as insurgents in the United Irish and 170 homes in Ballycanew

and Camolin and Fr. John Murphy's chapel at Boolavogue burned by the Camolin Cavalry.

These events signaled the true beginning of the "Rebellion";

27 May: (Whit Sunday) the United Irish rebels under Fr. John Murphy won their first victory at Oulart

Hill killing 106 of the North Cork Militia, really about 3,000 rebels armed with 40-50 guns,

pitchforks scythes and pikes and even stones defeated regular British Cavalry and Militia

killing six of their officers with a loss of only 6 men (one of which was piked by his own

companion who mistook him for a Yeoman because of a stolen red waistcoat); (An ironic

twist occurred after Oulart Hill when the defeated North Cork Militia men pleaded for mercy

in the Irish tongue which the Wexford rebels no longer understood, their language was

English, and the pleas fell on deaf ears. Now it is known that the family of Kathern Flynn

originated in the County Cork.)

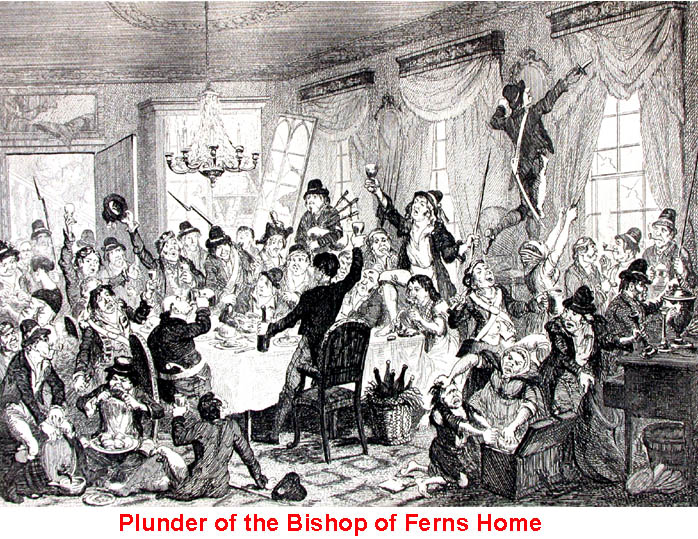

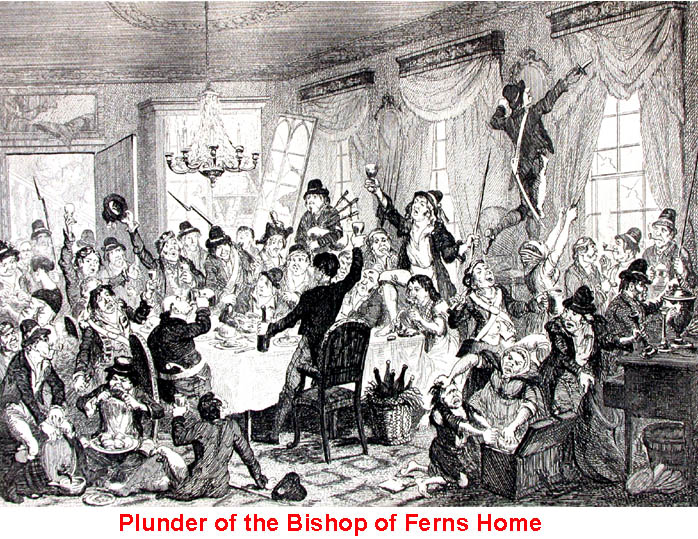

28 May: the insurgents march to Camolin and raided the home of Lord Mountnorris and on to Ferns

to sack the home of Dr. Cleaver, the Protestant Bishop of Ferns, it was here that Fr. Michael

Murphy and his followers from Ballycanew joined the rebels, the day was completed by the

rebels, now some 5,000 strong, taking the town of Enniscorthy where murder and pillage

were the order of the day;

30 May: saw the fall of the town of Wexford and declaration of the first "Irish Republic", here the British

garrison surrendered and fled to Duncannon to avoid the destruction and bloodshed that had

occured at Enniscorthy (35 Protestants being murdered in a Windmill);

1-4 Jun: saw the rebels suffer their first major casulties at Buncloddy and Tubberneering with the loss

of over 250 men as they attempted to take the town of Gorey;

5 Jun: a force of 20,000 rebels under Bagnal Harvey were defeated by 2,000 garrison troops in the town

of New Ross and they retreated back to their camp at Vinegar Hill outside Enniscorthy, here, in a

farmstead called Scullabogue, the second atrocity was committed, about 200 Protestant men,

women and children being held prisoner in the barn were suffocated, shot or piked to death as they

tried to escape when the barn was deliberately set afire, there were no survivors;

9 Jun: after taking Gorey, the rebels, mainly armed with scythes and pikes, continued north from their

camp, possibly through Ballycanew, and suffered their second major defeat at Arklow on the Dublin

road incurring heavy casualties due to a foolhardy mass attack on the garrison of 1600 soldiers;

20 Jun: 100 of the 300 odd rebel prisoners held in Wexford Jail were massacred on Wexford Bridge by

locals under Tom Dixon and his wife, they were shot or piked and thrown into the sea, this took

place after the main body of rebels had left the town for their camp on nearby Vinegar Hill in

preparation for their final battle;

21 Jun: the final chapter of the "First Irish Republic" was written when the rebels, were finally routed on

Vinegar Hill and a vicious slaughter by government troops took place, in all, the Wexford

Republic had fought 21 battles and nationwide rebel casualties numbered between 20-30,000

with a maximum of 3,000 inflicted by the rebels. Many rebel leaders were executed and other

exiled and a few actually escaped to France.

Below are two contemporary drawings of major events taken from an old book "The Revolution of

1798" written in 1823, plus a map detailing events that took place in the vicinity of Ballycanew.

When you examine the map and drawings on the previous pages and the one below, you can see

that the Langstaff's, and Warren's living in the vicinity of Ballycanew, were certainly exposed to the

full effect of the atrocities committed by both sides. Even though the drawings were done by

Protestant sympathizers and emphasized the cruelty to the Protestant captives and greatly distorted

and exaggerated the features of the Catholic participants they tell a chilling story of death and

destruction. As well one has to remember that of an estimated 30,000 people killed during the

rebellion, fully half were said to have been "killed in cold blood". This number should be compared

to the 40,000 deaths in the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution keeping in mind the fact

that France probably had 10-20 times the total population of Wexford. It is not known if our ancestors

did actually take part in any of these events or whether they were merely innocent observers. But all

things considered, these events are still sufficient reason for emigrating to a new home where land

would be plentiful and religious freedom was to be expected.

Let me end with a photo that will remind us that even today these fateful events are still

remember, at leats in Gorey where the photos were taken.

When you examine the map and drawings on the previous pages and the one below, you can see

that the Langstaff's, and Warren's living in the vicinity of Ballycanew, were certainly exposed to the

full effect of the atrocities committed by both sides. Even though the drawings were done by

Protestant sympathizers and emphasized the cruelty to the Protestant captives and greatly distorted

and exaggerated the features of the Catholic participants they tell a chilling story of death and

destruction. As well one has to remember that of an estimated 30,000 people killed during the

rebellion, fully half were said to have been "killed in cold blood". This number should be compared

to the 40,000 deaths in the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution keeping in mind the fact

that France probably had 10-20 times the total population of Wexford. It is not known if our ancestors

did actually take part in any of these events or whether they were merely innocent observers. But all

things considered, these events are still sufficient reason for emigrating to a new home where land

would be plentiful and religious freedom was to be expected.

Let me end with a photo that will remind us that even today these fateful events are still

remember, at leats in Gorey where the photos were taken.

The first was Fr. Michael Murphy who had been dismissed from the priesthood and was in contact with the United Irishmen and lodged in Ballycanew. On learning of the uprising the local Camolin Yeomanry burned his lodgings and shot his landlord. This event took place almost on the Langstaff doorstep (see townlands map above for distances, townlands are like our townships but generally much smaller and as you can see very irregular). Father Murphy is buried in the cemetery of St. Edans Cathedral in Ferns (see photo below).

The second was a Fr. John Redmond of Camolin (just west of Medophall townland), identified as an "orange priest" because of his anti-rebel sympathies. He was forced to take refuge in Protestant homes during the course of the rebellion. From these two individuals, one Protestant and one Catholic, one can see that no matter which side you were on, your life and the lives of your family were in constant danger. A chronological description of the main events of 1798 that took place in the vicinity of the Langstaff townlands follows: 30 Mar: Martial law declared over all Ireland and the local Yeomanry and Militia terrorize the people with scourging, pitchcapping (covering the head with pitch and setting it alight, common in Ferns, Gorey area), and half-strangulation;

When you examine the map and drawings on the previous pages and the one below, you can see that the Langstaff's, and Warren's living in the vicinity of Ballycanew, were certainly exposed to the full effect of the atrocities committed by both sides. Even though the drawings were done by Protestant sympathizers and emphasized the cruelty to the Protestant captives and greatly distorted and exaggerated the features of the Catholic participants they tell a chilling story of death and destruction. As well one has to remember that of an estimated 30,000 people killed during the rebellion, fully half were said to have been "killed in cold blood". This number should be compared to the 40,000 deaths in the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution keeping in mind the fact that France probably had 10-20 times the total population of Wexford. It is not known if our ancestors did actually take part in any of these events or whether they were merely innocent observers. But all things considered, these events are still sufficient reason for emigrating to a new home where land would be plentiful and religious freedom was to be expected. Let me end with a photo that will remind us that even today these fateful events are still remember, at leats in Gorey where the photos were taken.